Bringing news corrections further into the Digital Age: a new project

The ASU News Co/Lab is going deep on corrections. Not jails and prisons, but the mea culpas journalists offer when they’ve erred in their public work.

The ASU News Co/Lab is going deep on corrections. Not jails and prisons, but the mea culpas journalists offer when they’ve erred in their public work.

Forthright corrections and major updates are an essential kind of transparency. They’re also by far the most common form of post-publication fact-checking. But they’re still mostly done in traditional ways. We see lots of room for improvement in this area — and some potentially groundbreaking potential to help reduce misinformation’s impact.

So we’re embarking on a new project to help bring journalistic corrections firmly into the 21st century, in ways that lead to greater trust in journalism and, we hope, deeper connections between newsrooms and the communities they serve. Our partners include journalists, researchers, and technologists.

I’m old enough to remember what journalistic corrections looked like in the traditional media era of print and broadcast. In newspapers, corrections (when they were done) lived on Page 2, where they showed up days or weeks after the original error. They rarely contained enough context for the reader — even someone who’d read the original story — to understand what had happened. Broadcast radio and TV corrections were, and remain, almost nonexistent.

Then came the digital age. News organizations realized they could fix mistakes online, and append an explanation of what had happened. That limited future damage, since people who were new to the piece got the right information, but they didn’t do much for those who’d seen the error and moved on. And in a world of promiscuous social-media sharing, the problem was compounded.

Of course it’s best not to make mistakes in the first place. But journalists are a) human and b) deadline-driven. So we make mistakes. That’s unlikely to change.

What if we could do more than prevent future damage, by repairing the previous damage? That’s a key part of what we’re working on, and we have allies.

We’re going to work with top researchers, including Dartmouth’s Brendan Nyhan; technologists; and news organizations including three newsrooms, one of which is The Kansas City Star, from the McClatchy media company, where the idea for this project originated. We’ll do experiments, research, and — this is key — develop a software tool to make it easier for journalists to propagate corrections and key updates in ways that mirror the original posts and shares.

We’re grateful to Craig Newmark Philanthropies, and of course to Craig himself, for seeing how this might be possible — and for providing launch funding for this new project. Craig has been a passionate advocate for improving fact-checking and otherwise beefing up quality in the journalism ecosystem, and this fits directly into that goal. (At my blog, I’ve posted a few personal thoughts about Craig and his work.)

We’re grateful to Craig Newmark Philanthropies, and of course to Craig himself, for seeing how this might be possible — and for providing launch funding for this new project. Craig has been a passionate advocate for improving fact-checking and otherwise beefing up quality in the journalism ecosystem, and this fits directly into that goal. (At my blog, I’ve posted a few personal thoughts about Craig and his work.)

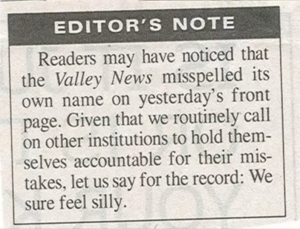

- This massive correction was the basis for a proof-of-concept test of moving fixes through social network.

This project started as a one-off experiment: to see if a journalistic correction could catch up, to the extent possible, to the original mistake in a social-media sharing environment. But that test was part of something bigger. We’re convinced, and reality is bearing this out, that transparency should be a core journalistic value.

An honest admission of an error is transparency. It’s not just the right thing to do. It can enhance trust when done right. It can lead to more engagement — by which we mean deeper conversations — among journalists and people in communities. We hope to demonstrate that it leads to more public willingness to support journalism as subscribers, members, and donors. (If your news organization is interested in this project, either as an observer or collaborator, let me know.)

We’ll be talking more about what we’re doing as the project proceeds, but here’s an outline of where we’re headed. We plan to:

- Gather and analyze the available research on journalistic corrections. We need to be clear what we know, what we don’t know, and what we need to know. We’re encouraged by a recent meta-analysis of research on correcting misinformation that found promising evidence that corrective messages that provide context alongside a retraction are effective. Look for our research roundup in the relatively near future.

- Build a tool that helps streamline the process of sending corrections (and essential updates) down the media pathways the original stories traveled. The tool will include research-oriented features that encourage experimentation, such as A/B testing to see what language gets the best results. We’ll be open-sourcing this work along the way.

- Consult with researchers and journalism partners. (If your news organization is interested in being part of this, let us know. We’re looking for collaborators that span various modes and styles of journalism. The key requirement is a belief in corrections, and willingness to experiment.)

- Convene a meeting with key researchers, journalists, and technologists who are working in this arena. One goal here is to develop an agenda that, we hope, will help the journalism craft as a whole modernize its attitudes about corrections and updates.

- Publish frequent blog posts to keep interested parties up to date.

Again, we’re grateful for Craig Newmark’s support in this project, as well as the Cronkite School’s ongoing support. And we’re optimistic that we can do something here that makes a difference.

Dan Gillmor is a longtime participant in new media and digital media literacy. He’s author of the 2009 book, Mediactive, discussing media literacy in the digital age from a journalist’s perspective.