How — and why — one NPR affiliate tracks the diversity of its sources

In 2017, Austin’s NPR affiliate station was dealing with some cultural issues.

“Folks were not happy about the way that we were approaching communities of color,” says KUT’s Projects Editor Matt Largey.

The station had just completed a project where they embedded in a historically Black East Austin neighborhood — one that was previously segregated and now was becoming gentrified.

“It brought up a lot of issues about how we approach coverage of communities of color and making sure that those voices are telling their own story. We wanted to make sure these folks are front and center in coverage of the things happening to them,” Largey says.

So, KUT’s staffers decided to track the diversity of its sources — including age, gender and race.

In late May, State Press Diversity Officer Farah Eltohamy and I chatted with Largey to learn more about the newsroom’s process and the audience’s response so far.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for clarity.

Question: Why did you decide to keep track of your sources?

Answer: We really wanted to quantify what we were doing. We really wanted to get some hard data to be able to say, “OK, here’s how we’re doing on this. Here’s how we’re reflecting the entire array of people in our community. And here’s how people are being represented in our coverage.”

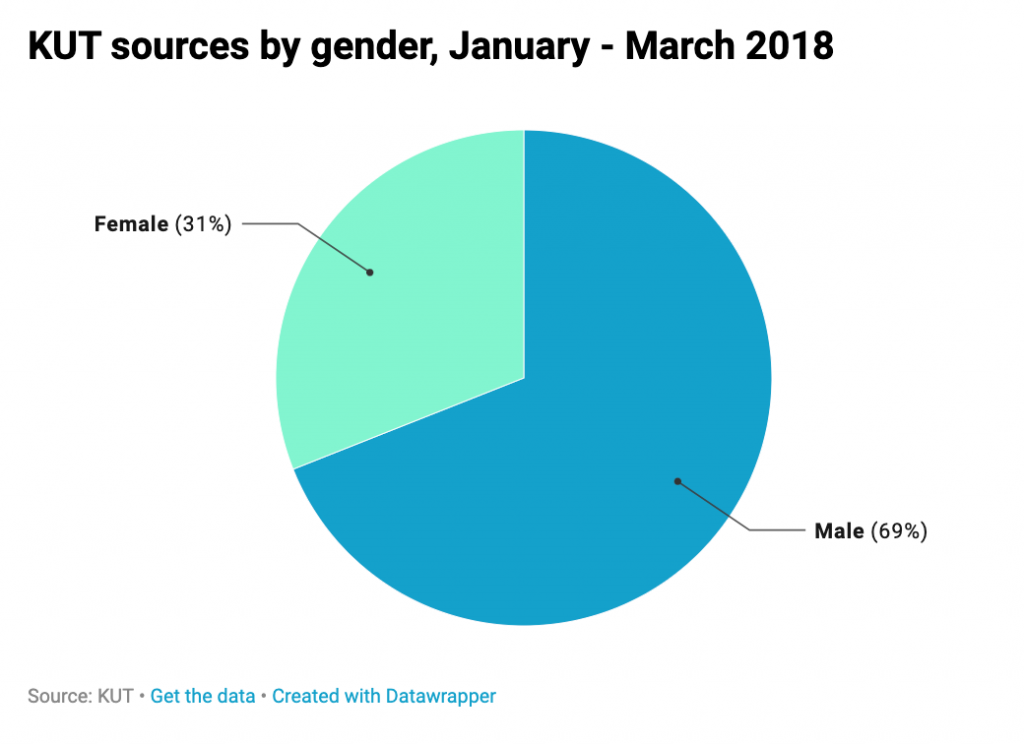

The only way we could really do that was to actually get the data, so we started with a baseline. We hired someone part time to do an audit of every single person we interviewed in a three-month span in early 2018. [Editor’s note: See KUT chart, right.]

That revealed some really big over-representations of men, and particularly white men. Some of that was tied back to who is in charge: The mayor is white. The police chief is white. We’re the state capital, and a lot of our state leaders are also white men. So that’s part of it. Those voices are going to be a part of our news coverage, but what about everybody else? Things are happening to other people in our city and in our region — we still need to make sure everybody’s stories are being told.

Q: What came next?

A: It took us a while to figure out how to wrangle all that data from those first three months and to draw some conclusions. In September, we started having reporters pay attention to the attributes of the people they were talking to: race/ethnicity, gender, age and location.

We did that for about a year. As you probably saw, we did quarterly updates along the way. And we saw ups and downs in the data from month to month.

We wanted reporters involved in the process so they could see how they were doing in real time. Am I quoting twice as many men as I am women? Why is that? Are there other sources that I could be going to?

In journalism there’s a tendency to talk to the person who picks up the phone first. That’s really not a great way of doing business. If you quote those people all the time, then your coverage is going to be skewed.

This is a way to encourage journalists to think differently about who they can approach and other sources they can cultivate. We heard some feedback from reporters that, yes, as they went along, it made them stop and think. It almost became like a competition to see who could get the better numbers. Beyond just measuring it, the other part was sort of influencing the behavior. Can you change something just by watching it? And I think there is evidence there that you can.

Q: I was going to ask if their habits shifted simply because they were aware.

A: Yeah, I definitely think so. And I will say, it depends on who you’re talking about.

It shifted for a lot of our beat reporters — folks who have more time to carefully consider who they’re going to go to. The newscast, quick-turnaround folks need a source fast, and they don’t necessarily have any control over who that source is.

It shifted for a lot of our beat reporters — folks who have more time to carefully consider who they’re going to go to. The newscast, quick-turnaround folks need a source fast, and they don’t necessarily have any control over who that source is.

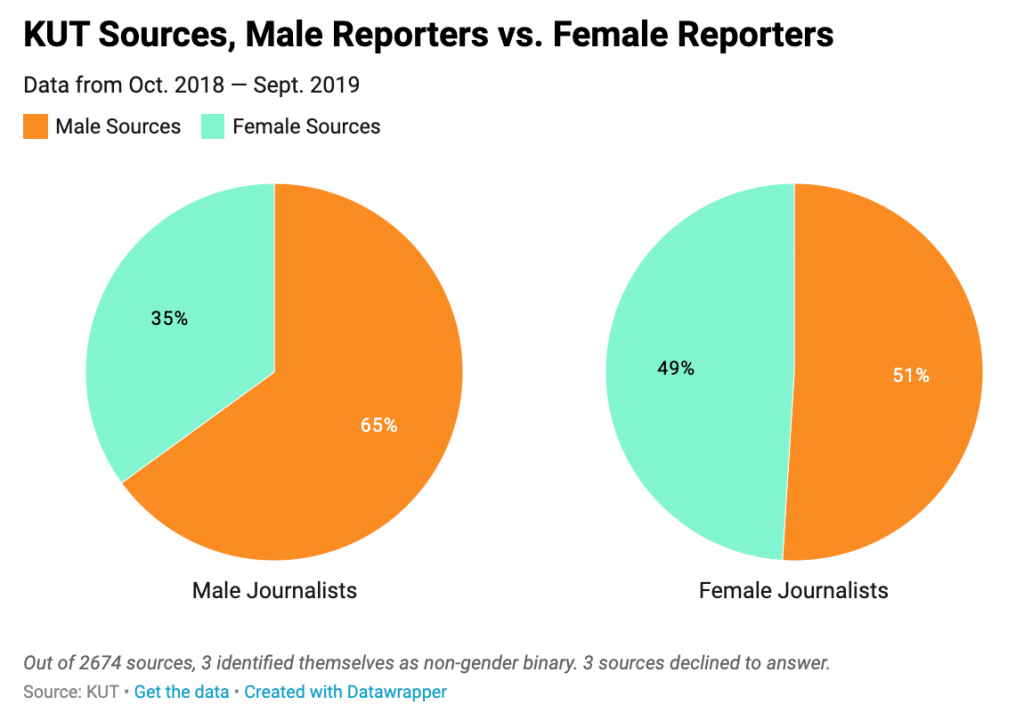

But I do think it shifted some people’s behaviors, particularly among our female reporters. We saw a real turnaround in the gender balance between male and female sources for them.

In our baseline, we were at almost 70 percent male sources, which is mortifying. But when we measured it over the year, our female journalists had an almost even split. So I really do think — and many of them would say this — it had made them think twice, and it made them more aware of who they were going to.

Q: What was the newsroom reception like?

A: There are about 20 of us in the newsroom. We have a fairly young newsroom, so we don’t have any real old timers. Our staff generally understood what we were trying to do and were supportive of that.

Q: And the catalyst came within your own newsroom after you realized some of your reporting was problematic, so I imagine that helped.

A: Definitely. It was borne out of conversations we were having within the newsroom. It wasn’t like our general managers said, “We need to do something about diversity!” Because I don’t think that works.

We needed to have some common understanding of what we were trying to accomplish —and that this wasn’t a chore, but that this had benefits for all of us, for the work we do and for the community as a whole.

To some degree, all newsrooms are public services. But we’re fortunate that we’re in public radio, which has a very strong culture of service — and KUT in particular. That really helped us get people onboard.

Now, I will say, while people might be on board, it might not be super easy to get them to do the work. There’d be many months where I’d be like, “All right, guys, it’s time. Here’s this long list of people who aren’t caught up on all of their sources in our giant spreadsheet.” And, you know, it would take some reminding, and not so gentle reminders.

The people who are best at this do it daily or right after an interview.

Q: Have the sources balked at these questions at all?

A: We have some boilerplate text that helps reporters explain why they’re asking for this information. “We’re trying to make sure that we reflect the diversity of our community, so I just wanted to ask you for some demographic information. This won’t be shared with the public. How do you identify your race or ethnicity? Age? How do you identify in terms of gender? What part of town do you live in?”

We encourage reporters to ask because you never know, and making assumptions can be really dangerous — or at least wrong. This is not public data in any way, so it’s not like someone would look back on the sheet and see that they’re misidentified, but it’s going to throw the data off if you’re wrong about that.

But anecdotally, I’d say 95 percent of people, if not higher, have no problem answering those questions. You get the occasional person who you know is white, but will say they’re Black. And it tends to be people who are more distrustful of the media. And sometimes they’ll just say, “No, I’m not going to tell you that. That sounds stupid.”

Q: What happens if someone won’t answer?

A: We note “declined to respond.” That’s a very small number of our sources. In our entire year’s worth of data, out of 2,674 sources, only three people declined to answer how they identify as for gender. Fifteen sources declined to respond in terms of race and ethnicity.

Q: You’ve been very transparent about the project and process — why? How has the public responded?

A: The feedback we got was overwhelmingly positive. We tried to be very clear about what we were doing from the beginning. Not only to give potential sources a heads up about these questions, but also as a way of holding ourselves accountable.

We went into it knowing we wanted to make the data public, no matter what it said. I had a hunch that the numbers weren’t going to be very good, and they weren’t. There were certainly a number of people who are like, “Oh, I’m not surprised. Public radio’s so white.” Or “Yeah, I hear too many male voices.” And those people are right. They’ve got the evidence that their hunches were correct, that all of our hunches have been correct.

But then a lot of people thanked us for doing this and for being transparent about it. It’s important to recognize this if you hope to do something about it. So I would say overwhelmingly, it was a positive response.

Q: A lot of projects like this start with good intentions but lose momentum. How are you going to ensure you continue? What are the next steps?

The magic in tracking

KUT hired part-time employee, Sangita Menon, to collect and analyze the baseline data in 2018. (Learn more about her methodology here.) Menon, a former engineer, created what Largey calls a “magic” spreadsheet to track the station’s source information.

The spreadsheet features a tab per reporter, plus a dynamic dashboard so the team can see how they’re doing in real time. Reporters the following information per source:

- Air date

- Story format

- Story category

- If the story deals with race

- Title

- Name

- Basic identifying information

- Race (and how it was identified)

- Gender

- Age range

- Expertise

- Location

While the team did try the Google form method — commonly used by other NPR affiliates — they returned to their trusty spreadsheet.

Why? “The problem with the form is that you can’t see what you’ve put it in the past — it just disappears into space,” Largey says. Even if reporters do have access to the sheet it’s connected to, who knows if they revisit it. “With our spreadsheet, you look at the gender column and see that it’s all male — you have a visual reminder of what you’re doing.”

A: The pandemic has somewhat thrown a wrench into all this. We’re still collecting the data. If it was not for the pandemic, I would’ve published a review of the first quarter data in March. I’ll probably do a six-month review, because I’m really interested to see the effects of the restrictions that the pandemic has placed on reporting — just in terms of not being able to just walk down the street and find a person you want to talk to.

At this point, tracking is part of people’s workflow. Having done it for a year, people are just kind of in the zone now. There are still people who wait until the end of the month to do it, and then there are people who do it on a daily basis. So I think we’re just going to keep going with it.

Something I would like to institute is being more consistent about sharing the data internally on a weekly basis. We don’t need to do a whole PowerPoint on it every week, but just quickly establish how things are going and keep it in people’s minds.

Q: Thanks, Matt. I hope more news outlets do this.

A: It seems hard at first, but once you get into it, it’s not that bad.

This is something journalists need to think about. It’s something that we are increasingly going to be required to think about as part of the job. The issue of representation is not going away; it’s only going to get more ingrained, I hope. I feel like people are finally starting to wake up to this.