Our new digital media literacy degree: A “user’s guide” to 21st century digital life

About two years ago, my colleague Kristy Roschke and I were contemplating the future of the ASU News Co/Lab and our related teaching of digital media literacy. One idea was to add another course or two, to give students more advanced and nuanced understanding of their role in our complex information ecosystem.

We took that idea to Chris Callahan, then the dean of ASU’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication and now president of the University of the Pacific. His reaction: “You’re thinking too small. This should be a degree.”

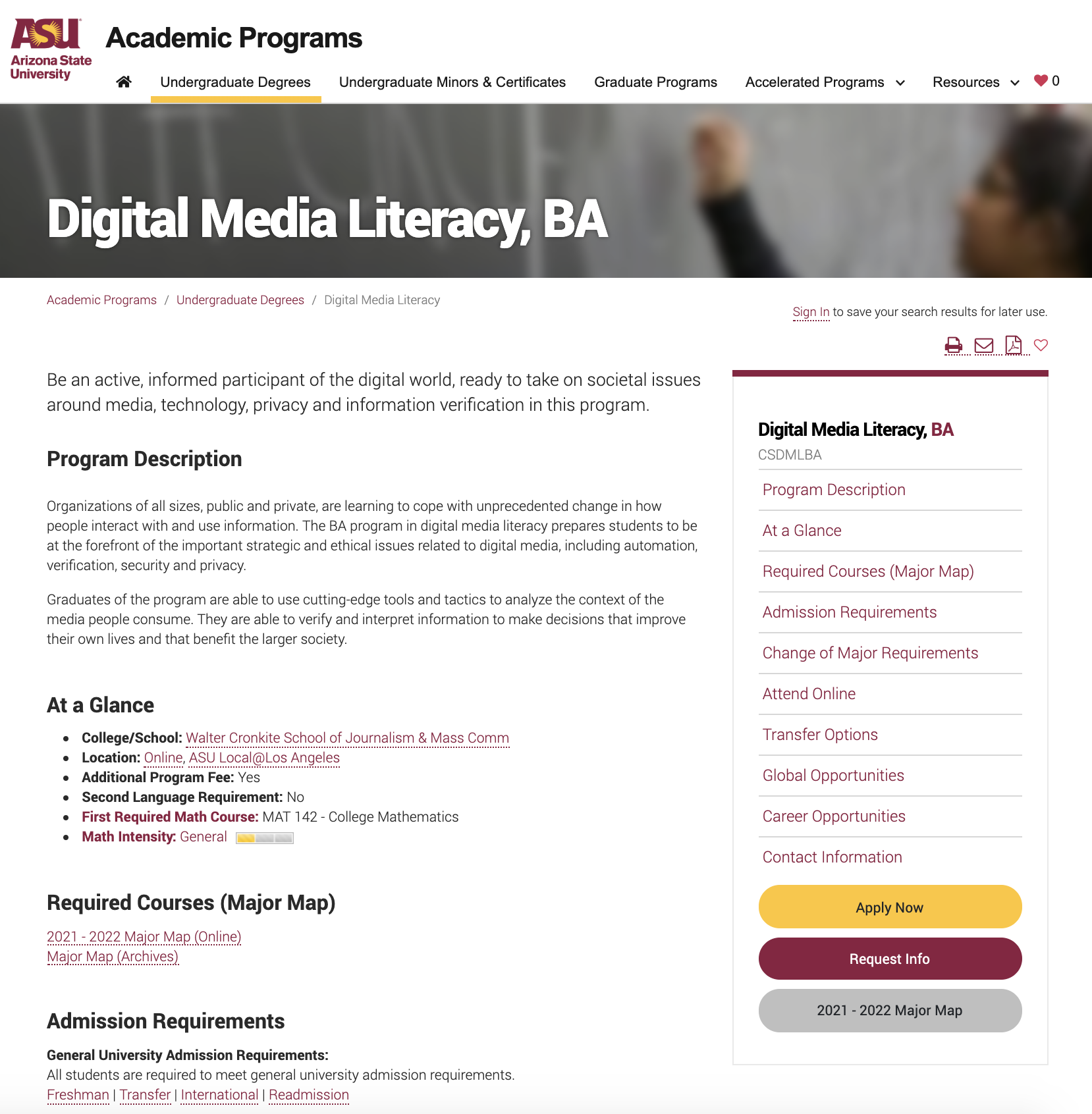

And so it will be this fall when the Cronkite School launches a new bachelor of arts in Digital Media Literacy. We have some powerful ambitions for the program — among them, applying what we’re learning from our News Co/Lab work to the classroom (and vice versa) — and we want to tell you more about how we see it shaping up so far.

And so it will be this fall when the Cronkite School launches a new bachelor of arts in Digital Media Literacy. We have some powerful ambitions for the program — among them, applying what we’re learning from our News Co/Lab work to the classroom (and vice versa) — and we want to tell you more about how we see it shaping up so far.

Why, you may ask, is this happening in a journalism school? As Jessica Pucci, associate dean at the Cronkite School, said in the new degree’s official announcement: “Media literacy is top of mind for the Cronkite School because a healthy society depends on it.”

The online degree program, like the courses we now teach in digital media literacy, is rooted in a fundamental reality. Digital information is embedded in much of what we see, say, touch and do. Our information systems have fundamentally changed, and we’re still catching up to the implications for individuals and society. And most of us could use some help, not just in understanding how it works, but equally important, participating with integrity. We’ll need to challenge ourselves, and the emerging communication systems, to meet responsibilities that are embedded in timeless values but have urgent modern requirements.

That’s what we will explore with our new degree: a challenging, interdisciplinary course of study that helps our students emerge from their studies better equipped to be active users of data and information, and leading contributors in civic life.

Some background and details

Our modern world is defined in part by increasingly unfettered access to knowledge. When people can quickly find useful, accurate information about health care, government, education, conflict, sustainability and many other topics, they can make better decisions and act on them.

But as we’ve seen repeatedly in recent years, the age-old problem of misinformation has become worse given the amount and velocity of news, entertainment, data and other forms of information. Lies spread fast and are often difficult to counter. Deceit threatens our communities — and our democracy.

No one doubts the need for a better information supply, not just more journalism but also — and maybe especially — adding integrity to what people post and share online. While improving the supply is crucial, so is upgrading us. This is the demand side of the equation, and media literacy is at the core.

When we say “us” we are not talking only about individuals. No matter who we are, and what we can do ourselves, we are part of a wider society. We also need to upgrade — in ways that promote honorable participation and equitable outcomes — our networks, systems and communities in this digital environment.

Top civics-minded institutions have seen the need. For example, in their report “Crisis in Democracy: Renewing Trust in America,” the Aspen Institute and Knight Foundation’s Commission on Trust, Media and Democracy called for a national effort to “provide students of all ages with basic civic education and the skills to navigate online safely and responsibly.”

As noted, that navigation goes beyond sorting truth from falsehoods, among other essential skills for media consumers. It is, vitally, also about participation in our media-saturated culture in ways that boost our civic roles as information users and creators.

One goal of our new bachelor’s program, which is the first of its kind in the United States, is to establish the Cronkite School as a leader in addressing this urgent challenge. The program is rooted in the valuable traditions of the liberal arts, with deep focus on critical thinking, interdisciplinary research, cultural awareness, ethical decision-making and problem solving. It will help students apply these skills in our increasingly diverse and complex digital media ecosystem — giving them a firmer grasp on how information and technology affect our personal, social and professional interactions.

We want our graduates to apply cutting-edge digital tools and tactics, which change all too rapidly, to enduring principles. We want them to probe and understand the context of what they encounter and use online. We want them to embed their media skills in forming the decisions that improve their own lives, and the future of their communities and our society.

Those principles and skills will be especially helpful, we believe, in workplaces. Organizations of all sizes, public and private, are learning to cope with unprecedented change in how we interact with and use information. We want to help our students be among these organizations’ most valuable people in sorting through the strategic and ethical issues related to the digital ecosystem.

New courses

To make this happen, we’re creating new courses, adapting existing ones, and planning research to make sure we stay on the cutting edge in this field.

Among the requirements we’ve set for the new degree at its launch are the following courses:

Digital Media Literacy I and II

The degree is rooted in two courses we originally offered as mass communication electives, Digital Media Literacy I and II. The first of these introductory courses looks broadly at the information ecosystem, helping students be more active, careful users of the media they encounter in their daily lives — including up-to-date security and privacy practices. The second course puts more emphasis on creating media in a variety of ways, and in general advances the principles and skills from the first one.

Misinformation and Society

A brand-new offering will go to the heart of the issue that sparked us to launch the News Co/Lab in the first place: misinformation and its effect on all of us. This course will explore the latest research in misinformation studies, propaganda and media manipulation, and the psychological and sociological underpinnings of misinformation. It will also explore related topics, such as algorithmic literacy. One of my long-range goals is that our efforts to combat the spreaders of deceit will someday make this course less essential.

21st Century Freedom of Expression, Assembly and Innovation

Several years ago, I created and taught a pilot course called “Freedom of Expression in the 21st Century.” It covered some history of (mostly American) free speech, and explored how technology had changed the way we exercise our freedom of expression — and how tech was changing the way we think about it. In this new iteration, we will examine the evolving nature of free expression online, including, for example, how technology platforms can favor greater protections for some while exposing others to harassment that can lead to self-censorship. Tech and tech policy don’t only affect freedom of expression; they also have a huge impact on our right (and ability) to assemble and innovate. Hence the new name of the course: “21st Century Freedom of Expression, Assembly and Innovation.”

Research Methods

Then there’s research and data, which we all need to understand better. We see media literacy as one in a group of related needs, some of which are subsets of others — news literacy, for example, is in most ways a part of media literacy — and which overlap. Our degree program will help students get a deeper understanding of the methods researchers employ to investigate important questions.

Students will choose from a large number of Cronkite School course electives, including Media Law, Data Visualization, Podcasting, Media Ethics and Diversity, The Digital Audience, and Political Communication, to reach the credits they need inside the school. The remaining credits will come from the kinds of courses that liberal arts students take in any solid program: history, sociology, political science and the arts, among many others.

When people ask me how to describe what we’re doing with this new degree, I sum it up this way: Think of it as a user’s guide to our modern digital life.

The knowledge, ideas and skills we intend to convey are changing, or growing more nuanced, in ways we can’t predict now. The certainty of change will mean ongoing adaptation of the program. The courses may have the same titles a decade from now — there will certainly be some new ones — but their contents will morph with reality, physical and digital.

We’re thrilled to be moving this forward, and hope you’ll let us know what we can do to make it better.

Dan Gillmor is a longtime participant in new media and digital media literacy. He’s author of the 2009 book, Mediactive, discussing media literacy in the digital age from a journalist’s perspective.