New grads: Beware LinkedIn scams

She was CNBC’s newest content creator. She’d make $45 an hour and start April 26.

It all started with a LinkedIn job posting. Then came an offer from Ryan Ruggiero, CNBC’s director of newsroom outreach strategy and initiatives. The new graduate accepted it immediately. After all, she says, she thought she “hit the jackpot” of first-time journalism jobs.

But it turned out to be a scam — one that cost her more than $2,000.

“No one expects job scams on LinkedIn,” the student says. “This wasn’t a Nigerian prince asking for money.”

College graduates are entering the job market when income-related scams are at a historic high, according to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). Americans reported 70 percent more job scams in the first quarter of 2020 compared to 2019. Why? More Americans than ever were struggling to pay their bills and looking for work because of the coronavirus pandemic. It’s clear scammers saw an opportunity: reaching out to people who need jobs with the information they want to hear.

And these ruses are more thorough and more convincing than you may think.

Setting up the scam

The ASU Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication student was weeks away from earning a joint bachelor’s and master’s degree when she applied for the CNBC content creator position using LinkedIn on April 16.

The professional networking site was her go-to job searching tool. It’s quick, it’s convenient and it’s already connected to your resume-like profile.

Three days later, a job proposal came to her spam folder — as non-spam emails sometimes do, she explains. It was from Ryan Ruggiero at hm@cnbc-careers.com.

“He’s a real person at CNBC, he has a verified Twitter profile. The email had his photo, his signature and everything,” she says. “It looked legitimate.”

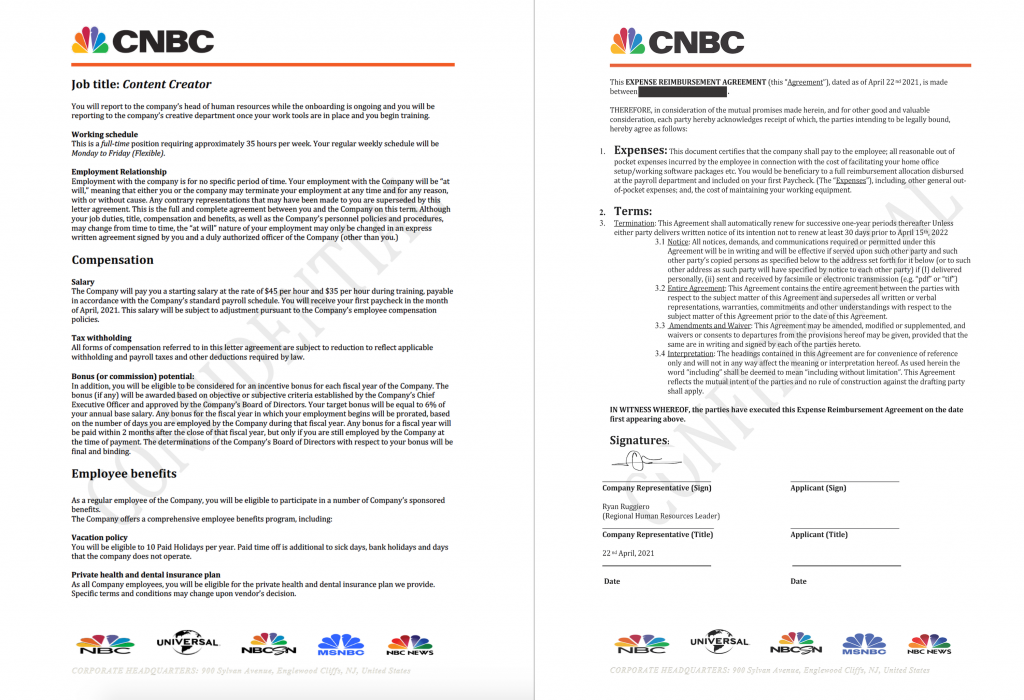

The email (see screenshot to the right) contained a “pre-job briefing” attachment that outlined the job’s description, responsibilities, compensation and benefits. It featured Ruggiero’s signature at the bottom. The next step: Contact Samantha Nelson to schedule an interview.

The email (see screenshot to the right) contained a “pre-job briefing” attachment that outlined the job’s description, responsibilities, compensation and benefits. It featured Ruggiero’s signature at the bottom. The next step: Contact Samantha Nelson to schedule an interview.

The two talked on Wire.com, a legitimate encrypted chat app that seems to be a scammer favorite. The student was expecting a video or voice call, but instead Nelson launched into the interview through text. She figured it was a preliminary screening interview.

“There were points where I wondered if she was a bot. The interview felt so disconnected from reality — she would send questions in batches of two and three. I didn’t know what to think, but I was already in it, so I figured I might as well finish the interview,” she says.

Then Nelson told her to cross her fingers.

She received the job offer from Ruggiero three days later. This time, she received a letter of agreement, a direct deposit form and expense reimbursement agreement. Her Form W-4 and company ID card would come in the mail.

She says, “I forgot about my suspicions about the chat interview because I was so elated about landing a job at CNBC.”

The execution

The new grad was to start just 10 days after she initially applied for the job.

But first, Nelson said they needed to set up her work equipment — an iPhone 12, iPad and MacBook Pro — with CNBC’s proprietary software. But there was one issue: CNBC was experiencing payroll issues, Nelson said. Could she pay the vendor for the software install? CNBC would reimburse her. This made her uncomfortable, but she had already signed an offer letter and a reimbursement form.

She received an invoice from the vendor, then sent them $1,000 using People Pay, a common payment system through her bank. She asked for a confirmation and got one — but the name on the email didn’t match who she thought she was paying. She continued her Wire discussions with Nelson, asking questions about her new position.

The more she thought about the situation, the more she started to question it. “Why did they want me to send the money? This is a big company with deep pockets,” she explains. “I just spent the weekend going back and forth thinking, ‘Is this real?’”

The new graduate received this job description and reimbursement agreement.

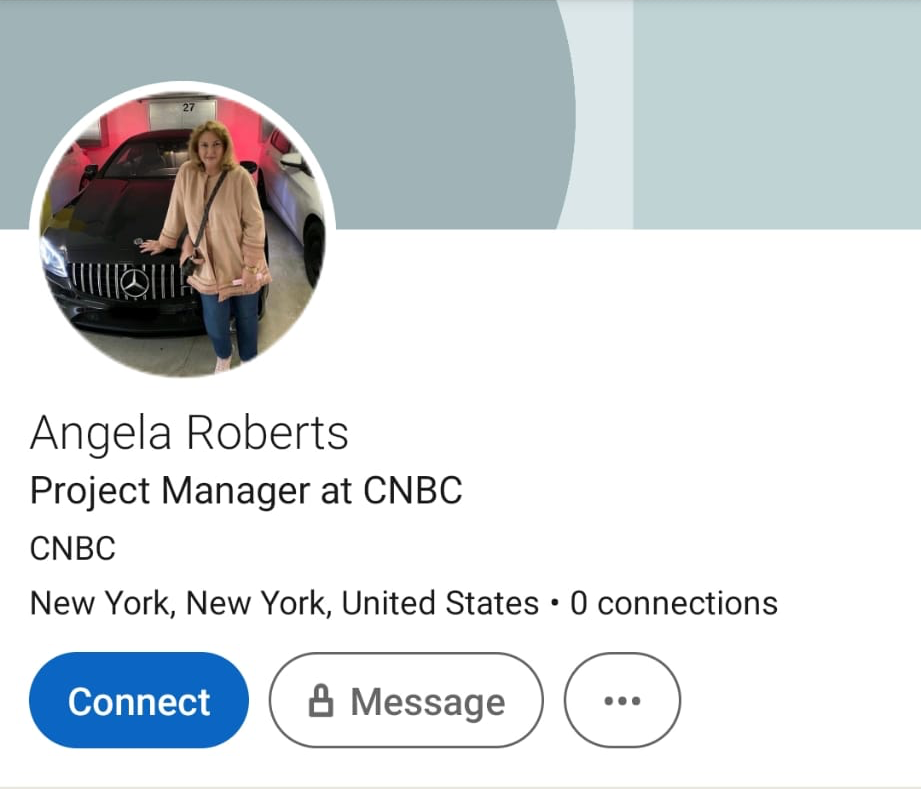

During that time, she put her journalism degrees to use and did some digging. She knew Ruggiero was a real person, but she still tried to verify his (or any other) CNBC email address online. No luck, but she did fill out the company’s contact form asking to confirm the offer. Even asking felt “pretty embarrassing,” because what if it was real? She also went back to the original LinkedIn job posting and saw it wasn’t Nelson who had posted it, but an Angela Roberts — but they had the same photo.

Clearly, the warning signs were there. But she continued to receive positive reinforcement from her family and friends, who were all hoping for the best.

“Anyone who I had brought up my suspicions to just chalked it up to imposter syndrome. They all said things like, ‘No don’t think like that. You totally deserve this. You’ve accomplished so much,’” she says. “I just thought maybe I’m overthinking this.”

On what was to be her first day on the job, Nelson came back with another demand: The iPhone 12 and iPad Pro were out of stock, and she would need to pay the vendor $1,150 for the discounted tech.

She paid the final $1,150 to the same email, again using People Pay. The gravity of the situation started to set in, and she asked a tech-savvy friend, “How do I know for sure that this email address belongs to CNBC?” Within minutes he had an answer: The domain had been registered only a month ago.

She had been scammed.

“Worse than the loss of money is that I’m graduating without a job now. If I do get any kind of job offer in the future, I’m going to be very, very paranoid about it.”

Staying safe on the job hunt

This isn’t the only type of income-related scam, but it’s one of the most common. Many involve fake checks; the “employer” sends a check, but asks the employee to buy gift cards or pay a vendor for something like home office supplies. The employee deposits the check, sends the gift cards — and eventually the bank identifies the check as a fake and you’re out that money. These scams are three times as likely to affect adults in their 20s, according to the FTC. Others hinge on multi-level marketing schemes or promise big bucks through investment seminars.

Regardless, scammers are meeting people where they’re searching for jobs, like LinkedIn, or impersonating hiring managers like Ruggiero or even college career services departments.

Educating yourself on these job scams is the best way to avoid them. If you’re unsure whether a job offer you’ve received is legitimate, the Cronkite School graduate outlines a few tips and red flags to note.

1. Trust the spam folder. Sometimes real emails slip through, but it’s there for a reason. Don’t just assume that a spam email will be a random jumble of letters and numbers. “Look at the email address and know that scammers are very crafty people and it’s going to seem very realistic,” she says.

2. Use a reverse image search. Sometimes a LinkedIn profile will have obvious warning signs: lots of spelling errors or not many connections, for example. Trust your instinct and take the next step with a reverse image search. Has the photo been used elsewhere? Check the name, industry, date, location and any other context clues that could tip you off. In the case of the CNBC scam, the scammer used the same photo for two different people: Samantha Nelson and Angela Roberts.

2. Use a reverse image search. Sometimes a LinkedIn profile will have obvious warning signs: lots of spelling errors or not many connections, for example. Trust your instinct and take the next step with a reverse image search. Has the photo been used elsewhere? Check the name, industry, date, location and any other context clues that could tip you off. In the case of the CNBC scam, the scammer used the same photo for two different people: Samantha Nelson and Angela Roberts.

3. Enlist the help of a tech-savvy friend. Who owns the email domain? Is it consistent with the rest of the organization? Some internet digging can help you determine if that email address is legitimate and matches the company’s nomenclature. If you find the company’s emails are firstname.lastname@company.com and the email you received is firstname@companyHR.com, be wary.

4. Reach out to someone at the company. The company in question likely has a dedicated HR department or employee. Try contacting them to verify the person you’re talking to — and the job in question — is a legitimate representative of the organization.

5. Don’t give anyone money. Just don’t. That goes for sensitive personal information, like your social security number, too.

6. Report it. The student immediately reported the scam to LinkedIn, her local police department, the Arizona Attorney General and her bank. She even tried contacting Ruggiero through social media to let him know his likeness was being used. The FTC also recommends filing a report, which is shared with various law enforcement agencies, and LinkedIn recommends these tips.