Telling the community’s story through food

The Center for Collaborative Journalism’s Sonya Green explains how food writers are addressing crucial challenges in their communities.

Food brings people together. If there are barriers, food can break them down. I experienced this over and over at the Association of Food Journalists national conference in Phoenix in September.

The star of the conference was the exquisite presentation of Arizona’s best foods created by its brightest chefs, including James Beard Award winner Nobuo Fukuda of Nobuo at Teeter House and Barrio Cafe’s Silvana Salcido Esparza. However, the content of the conference was just as memorable as the meals.

Food writers take their craft very seriously. The job of a food writer is more than tasting food, reviewing restaurants or trying out the latest kitchen gadgets. Food writers document history. The infamous saying that something is “as American as apple pie” is no accident. It centers food as something Americans and all people have in common. However, inadvertently, the phrase also provides a window to discuss the ways in which we are different because for some the phrase can be problematic or emblematic of the American way. Writers can bring context to our shared food history and honor the nuance of our differences. They also celebrate food while being critical of equity and access.

The Center for Collaborative Journalism at Mercer University — along with our partners at the Telegraph and Georgia Public Broadcasting — recently embarked on an academic year-long project, Macon Food Story, that will continue the tradition of telling our collective food history with a focus on southern food culture.

The project will also look at food through the lens of access and health, with the help of News Co/Lab-sponsored reporter Samantha Max. (Find more of the Report for America community reporter’s work here.)

Food insecurity, food deserts and health outcomes are growing concerns in central Georgia. Macon Food Story aims to tackle these issues and provide examples of what some communities are doing to address the challenges. And reporters like Max are working directly with the community to discover what stories are important to them, involving them in the reporting process.

The questions about how to tell the stories of southern food history, culture, access and health in Macon are no different than those other cities face. At a panel on inclusive storytelling, Arizona Republic reporter, Dianna Náñez, offered this piece of advice, “Diversity is not separate from news; diversity is news.”

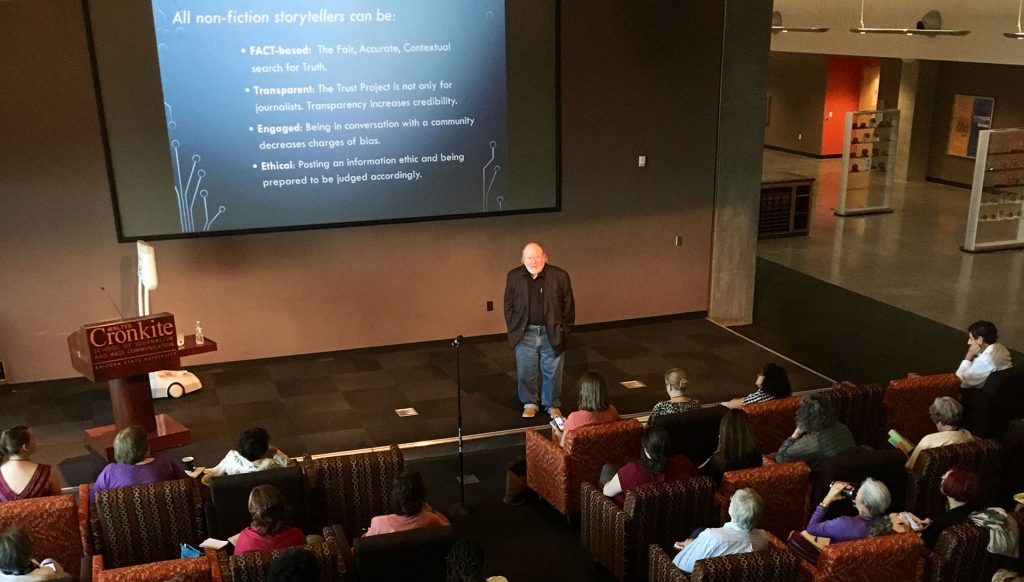

In his presentation, ASU professor and News Co/Lab Co-Founder Eric Newton provided an analysis that showed how food and news are really one in the same. He reminded us that news feeds the mind. Food feeds the body. There is junk news and comfort news. There is junk food and comfort food. Get the picture?

Food is an essential part of our collective history because food is life. Food writers play a vital role in documenting America’s history. There is a lot to chew on (pun fully intended).