Journalism corrections in theory and practice: It’s complicated

Several forces complicate news organizations’ efforts to correct information. Among them:

- In a 24/7, social media news environment, corrected stories never achieve the reach of the original story

- Different social media platforms have different capabilities (no editing posts in Twitter, for example), requiring multiple workflows

- Possibly most vexing, even after someone sees a corrected story, the misinformation is often what persists in their memory.

The negative effects of misinformation can greatly influence what someone believes about a topic regardless of a successful correction. Those effects can be even more pronounced in topics such as politics, though researchers have found evidence that some measures (more on that below) are effective in correcting the record.

As noted, we haven’t found a lot of recent research on how news organizations approach corrections. To help gain a better understanding, we’re in the process of collecting, and plan to share, written policies and best practices.

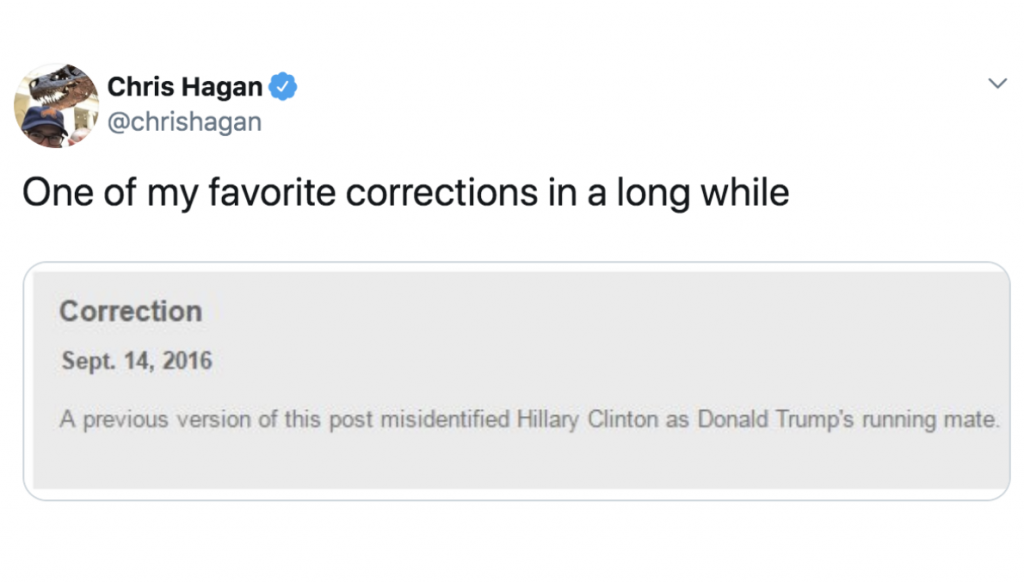

Journalistic corrections are often categorized as low impact — typos, misspelled names, dates — or high impact — factual errors, misinformation, myths. Whether or not a correction is low or high impact can determine how journalists handle the correction. Though striving to correct all mistakes to improve accuracy and credibility is an important goal, the research we’ve included in our review focuses on high-impact corrections. Because of the relative dearth of research on online news corrections, we also included in our review research related to correcting misinformation in other forms, such as fact-checking. From a scan of more than 50 articles, we’ve included 20 journal articles in our full research review.

From that selection of articles, several themes emerged that serve as practical recommendations for journalists.

1. Reduce mentions of the misinformation.

Avoid attracting further attention or generating additional arguments around the misinformation. The more details that appear to support the misinformation, even wrongly, the more likely the false belief will stick in recipients’ memories or create motivated reasoning to reject valid corrections. Several studies demonstrated that it is very difficult to correct false beliefs, especially when it comes to political news. In some specific cases, most notably related to partisan politics, a correction may even cause someone to dig deeper into their belief of the misinformation.

2. Create what researchers call “coherence” with the corrective message to induce healthy skepticism.

The stronger the alternative explanation in a correction, the greater the chance to overcome motivated reasoning. News organizations should provide as much detail about the new information as possible, but be careful about contextual cues that might undermine the message (i.e. an accompanying photograph that contradicts or misrepresents the correction). It is also important to correct information as soon as possible to increase recall of the updated information.

3. Provide credible sources in the correction.

Citing credible sources in a correction can help audiences accept the new information. Keep in mind, political public officials are not always trusted as much as expert sources in the fields of health and science. Still, research published in Science Communication found that corrections from a credible source can successfully reduce misperceptions.

4. Know your audience.

Understanding which stories get the most engagement on social media and who is tweeting and sharing them allows news outlets to leverage these gatekeepers when trying to get a message out into the public sphere. Demographic factors play a role in fact-check sharing behaviors. Research published in Communication Monographs in 2018 found that older people and those who identify as liberal tend to share corrective information more than others. Certain social network users keep each others in check by correcting each other on social media. Examining these digital audience behaviors will help when crafting corrective messages.

5. Use different platforms and modes.

Reach has a lot to do with getting users to share corrected information across social media platforms, but getting corrective messages into high-visibility areas on social media also increases the odds of acceptance. Encourage users to “share the facts.” Information campaigns, as opposed to single, one-time corrections, are also more effective when they are curated and aggregated by many different outlets. When possible and relevant, incorporate video in the message since this format has been shown to be more effective than long-form articles. Research shows corrections on social media are most effective when they are shared by “friends” or people within one’s social network. Automating a correction process or alerting people of corrections may help in getting the word out that a story has updated information (this is what the News Co/Lab will be doing as part of our project).

News outlets can increase their influence by encouraging recipients to share corrected information, engaging with them in the correction process. This process would need to distinguish between high- and low-impact corrections so as not to inundate the recipient with too much information.

For now, the research is mixed on whether corrections are effective in changing what a person knows about a topic. But several studies in our review do offer reasons for optimism. For that reason, even beyond the principle that corrections are an essential part of transparency and integrity, we hope the journalism industry will continue to develop better and more effective corrections.

The News Co/Lab’s corrections initiative aims to be part of that development. Our work will include an online tool to make it easy for journalists to send corrections down the same social media pathways as the original mistakes. But our overall goal is to help bring corrections and major updates firmly into the digital age. We’ve described that project here. If you have feedback or are interested in helping, please let us know.

Gail Rhodes is a teaching associate and PhD student at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism at ASU. Rhodes has over 16 years of professional experience as a television news and sports anchor/reporter. After graduating from the University of Illinois, she spent the bulk of her career in Chicago, reporting for Fox Sports and NBC Universal. She hopes to complete her doctoral degree in 2020.